Glycine is the body’s smallest amino acid — but its influence may extend from sleep regulation to metabolic health and even mitochondrial ageing.

If you’ve taken collagen supplements, it’s probably contained glycine. Each night when you fall asleep, glycine is helping you get there. A prominent focus of nutritional research into schizophrenia, diabetes, and more recently, mitochondrial ageing, glycine — the body’s smallest amino acid, is quietly rising in prominence in the biohacking community.

Glycine isn’t new. It was discovered in the 1800s, and most biochemists would place it somewhere in the background of metabolism — structurally essential, but not especially newsworthy. Yet over the past two decades, glycine has started to turn up in a surprisingly wide range of physiological roles: neurotransmission, inflammation, circadian regulation, insulin sensitivity, and even mitochondrial maintenance.

So is glycine simply versatile? Or is it playing a more central, underappreciated role in how the body balances input and output — excitation and inhibition, energy and repair?

Not just a building block

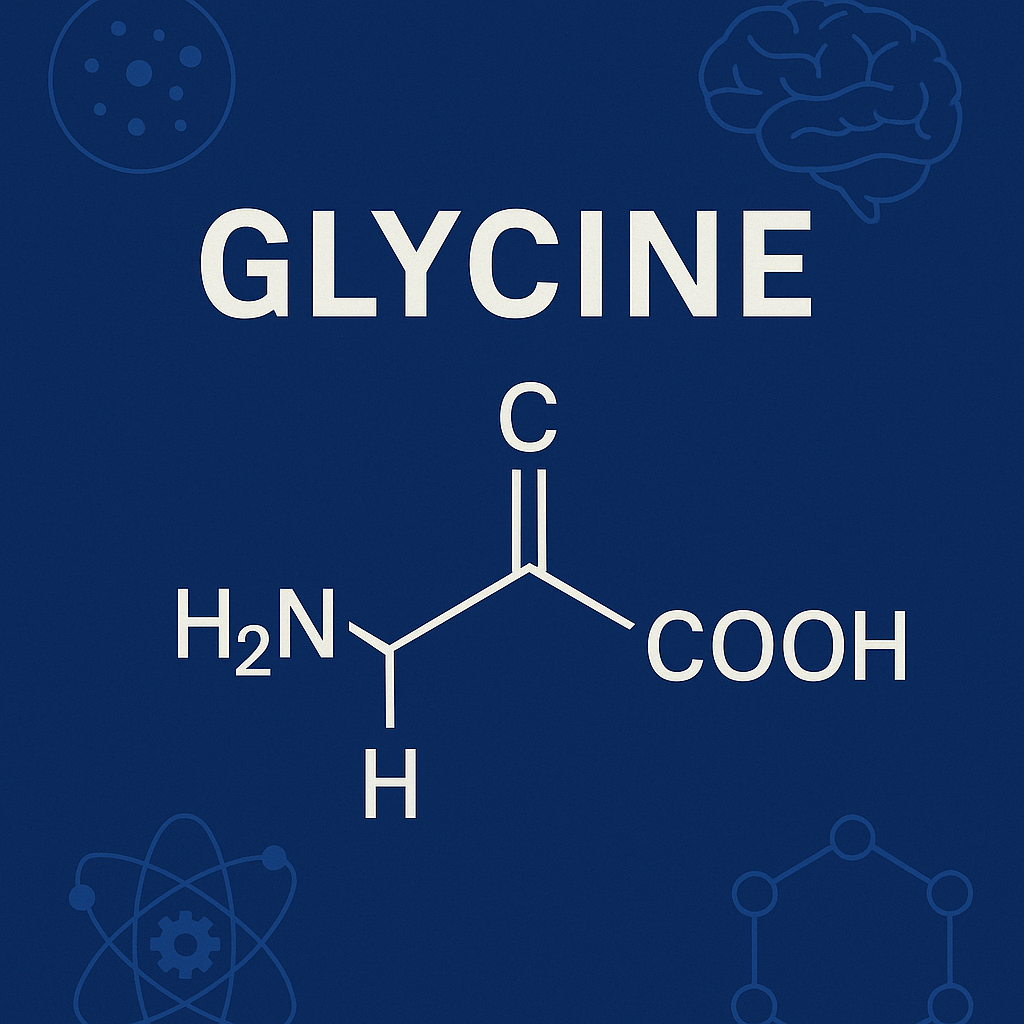

At its most basic, glycine is a component of proteins. It features heavily in collagen, where its small size allows the tight, triple-helix formation that gives skin and tendons their tensile strength. But in free form, glycine also acts as a signalling molecule. It functions as an inhibitory neurotransmitter in the spinal cord and brainstem, and as a modulator of excitatory glutamate signalling in the cortex.

At the NMDA receptor — a central site for synaptic plasticity and memory formation — glycine acts as a required co-agonist. In other words, glutamate won’t fully activate the receptor without glycine present. This has made glycine an occasional pharmacological adjunct in trials for schizophrenia, particularly in targeting negative symptoms such as emotional blunting and social withdrawal.

Cooling the brain, deepening sleep

One of glycine’s more reproducible effects in humans is on sleep quality. In several small trials, people who took around 3 grams of glycine before bed fell asleep faster, reported more restorative sleep, and had less daytime fatigue. Unlike sedatives, glycine doesn’t induce sleep directly. Instead, it lowers core body temperature — a key physiological signal that facilitates sleep onset — and appears to influence hypothalamic sleep-wake centres.

This thermoregulatory effect has drawn interest in circadian biology, where internal temperature rhythms are increasingly seen as part of the brain’s timekeeping mechanisms.

An anti-inflammatory buffer?

Glycine also seems to participate in regulating inflammation — not by blocking it outright, but by modulating immune cell excitability. Certain white blood cells, such as macrophages and neutrophils, express glycine-gated chloride channels. When glycine binds, these channels open, hyperpolarising the cell membrane and making it less likely to fire in response to stimulus.

In animals, this has been shown to reduce injury from inflammation, particularly in the liver, gut, and lungs. In humans, the evidence is early, but low plasma glycine levels are consistently observed in people with type 2 diabetes, obesity, and metabolic syndrome.

Glycine is also a precursor for glutathione, one of the body’s key antioxidant defences. This raises the possibility that chronic glycine depletion in metabolic disease reflects a wider imbalance in redox regulation.

Ageing and the GlyNAC protocol

More recently, glycine has been studied in combination with N-acetylcysteine (NAC) in older adults — a pairing known as GlyNAC. Together, the two amino acids supply the key substrates for glutathione synthesis. In a 2021 pilot study, adults aged 60–80 who took GlyNAC for 24 weeks showed improvements in mitochondrial efficiency, oxidative stress, insulin resistance, and even walking speed.

It’s an early study, and much of the work remains exploratory. But it adds to a growing sense that glycine may play a role not only in moment-to-moment regulation, but in long-term metabolic and cellular resilience.

A systems molecule?

What makes glycine intriguing is not any one dramatic effect, but rather the range of processes it appears to influence: sleep initiation, synaptic modulation, redox buffering, immune reactivity, structural repair. It’s difficult to classify glycine as simply a neurotransmitter, structural amino acid, or metabolic intermediate — it behaves more like a systems-level regulator.

Whether this translates into meaningful health interventions remains an open question. As with many molecules that sit at the intersection of multiple pathways, the benefits of supplementation — if any — may depend on context: metabolic state, ageing status, circadian disruption, or underlying inflammation.

Still, for a molecule often overlooked in favour of its flashier counterparts, glycine has quietly earned a place in the broader conversation about how the body maintains balance.

Further reading:

Inagawa et al. (2006). “Improvement of sleep quality in humans by glycine ingestion.” Sleep and Biological Rhythms. Shenoy et al. (2021). “GlyNAC improves multiple aging hallmarks in aging humans.” Clinical and Translational Medicine. Newgard et al. (2009). “A branched-chain amino acid–related metabolic signature differentiates obese and lean humans.” Cell Metabolism.

My Wellness Doctor

Leave a comment